- Home

- Alen Meskovic

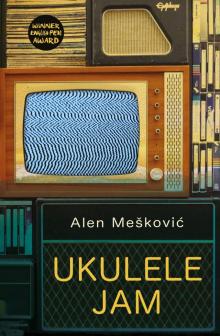

Ukulele Jam

Ukulele Jam Read online

UKULELE

JAM

Seren Discoveries

A series of translated literature introducing leading authors writing in ‘minoirty’ langauges ofr from ‘peripheral’ cultures. It includes work from Albanian, Basque, Welsh, Québécoise, Danish, and Czech, and from The Netherlands, Francophone Haiti, Luxembourg and Bosnia

Tony Bianchi – Daniel’s Beetles

Petr Borkovec – From the Interior

Gil Courtemanche – The World, The Lizard and Me

Fatos Kongoli – The Loser

Yannick Lahens – The Colour of Dawn

Jean Portante – In Reality

Kirmen Uribe – Bilbao - New York - Bilbao

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd,

57 Nolton Street, Bridgend, Wales, CF31 3AE

www.serenbooks.com

facebook.com/SerenBooks

Twitter: @SerenBooks

© Alen Mešković, 2018

Translation © Paul Russell Garrett, 2018

www.paulrussellgarrett.com

The rights of the above mentioned to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act.

ISBN: 978-1-78172-342-5

Ebook: 978-1-78172-343-2

Mobi: 978-1-78172-344-9

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without

the prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher work with the financial assistance of the Welsh Books Council.

This translation of Ukulele Jam is supported in part by the Danish Arts Foundation.

The book has been selected to receive fnancial assistance from English PEN’s ‘PEN Translates!’ programme, supported by Arts Council of England. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of idea. www.englishpen.org

Printed by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

Contents

Cassette 1 · PANORAMA BLUES

Cassette 2 · MIKI’S SCORING SONGS

Cassette 3 · THRASH & HEAVY

Cassette 4 · SOLO PASSAGES

Cassette 5 · NEW NOTES

Cassette 6 · PUNK’S NOT DEAD

Cassette 7 · BIG HITS OF SUMMER

Cassette 8 · HARD TURD MACHINE

Cassette 1

PANORAMA BLUES

PLAY

The bus pulled out of the station. Dad scratched behind his ear and coughed:

‘He gave us a hundred marks.’

‘I saw,’ Mum said.

‘He’s all right, my brother. In spite of everything.’

‘I don’t even know why the two of you argue. He opened his home to us. He helped as best as he could.’

‘Because he does not understand a bloody thing about politics! Besides, we do not argue. We discuss.’

Next to me, behind Dad, the seat was empty. One of our bags was resting there, but still I kept seeing Neno sitting there. I imagined we were still together, he and I, Mister No and Captain Micky.

Neither of us had a clue where the other was any more.

A month earlier, after Mum, Dad and I crossed the Croatian border and left Bosnia behind, Uncle had been waiting for us at that very station. Back then we still had some hope that our hometown would not fall, that the war would soon be over – that Neno and the others would soon be released. Now the ruins of the entire town were in Serbian hands, the front line had been pushed back, and it was clear to everyone that the war was not going to be over in a matter of weeks. My uncle, who had lived abroad for years but had returned to enjoy a retirement by the sea, believed the war would not be over until the summer ended.

‘Just wait till their balls start to freeze,’ he said. ‘Then they’ll change their tune.’

‘The people giving the orders do not have to sit in the trenches,’ Dad said. ‘That is the whole point.’

Mum’s dark curls and Dad’s shiny egg dominated my view the entire trip along the coast. I was still having difficulty turning my head to the right. The pain came and went as I looked out the window.

‘Emir?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Do you remember the time we came here on holiday?’

‘No.’

‘He doesn’t remember a bloody thing,’ Dad said. ‘He was too little. Little Miki, we called him back then.’

‘You were on a donkey. We took a picture of you riding it.’

‘Oh, okay. Wow.’

White facades, small stone haciendas, hotels and even more hotels lined the road. Tourists, well aware that the war had not reached everywhere in Croatia, were enjoying the hot July day. Their burnt shoulders, inflatable animals and beach balls kept my mind busy for a while. Then he turned up again.

‘Dear Mister No. I know you’re still alive. No matter what they say, I know that one day you’ll come …’

We had added his name to a number of lists, and Dad had contacted acquaintances with varying levels of influence. Everyone wanted money but no-one knew a thing. As of yet, nobody from his group had been exchanged. The politicians talked and talked, the soldiers shot and shot, and no matter where I was, there was a gaping void at my side.

The most optimistic of all the rumours suggested that they had been sent to a concentration camp in the vicinity of Banja Luka. The least optimistic went that the group had been executed the day they were separated from the rest of us.

‘People talk,’ Dad whispered. ‘If you hear anything, tell me. Understood? She spends enough time crying as it is.’

Mum cried a lot during our month at Uncle’s place. His flat was not particularly big, and I was bored most of the time. A stressed-out blonde at the Red Cross eventually found us a room at the camp in Majbule. None of us had ever heard of the place.

‘It’s well situated,’ she assured us. ‘Right by the sea.’

‘I don’t give a damn about the sea,’ Dad said. ‘I want to go home.’

According to the map, Majbule was a speck of flyshit about six kilometres south of Vešnja. I found it in Uncle’s thick, German atlas. Definitely not the kind of place you just happened to drive past. It was at the tip of a peninsula. The Balkini peninsula, it read.

While I studied the map, Dad and Uncle discussed the war and the time that preceded it.

‘The communists lied,’ Uncle said. ‘Far too much and for far too long.’

‘If it weren’t for us, there would have been a bloodbath ages ago. If it weren’t for the party, half the population wouldn’t be able to read or write!’

‘You all just marched in step.’

‘Yes, and why are you grumbling? You just up and left.’

‘Exactly! And then I invited you to join me.’

That was news to me. I closed the atlas:

‘Is that true?’

‘Yes,’ Uncle nodded. ‘He sent me a dismissive letter in return. No way was he going to clean toilets for the Germans! And Canada was too far away. He was not going to abandon his colleagues at the factory, his fishing trips, his football club.’

‘I was fine where I was,’ Dad said.

Uncle shrugged despondently:

‘That town’s always been a hole!’

We got off the bus in Vešnja. On the local bus to Majbule, Mum and Dad started chatting to an outspoken woman by the name of I

vka. It turned out that she lived in the camp. Her husband worked for the police, and they had a room facing the sea.

‘Most of the rooms have a balcony,’ she said. ‘There’s a beautiful peninsula and an island. You’re going to love it. Especially if you get a room facing the sea.’

‘The sea stinks of rotten eggs,’ Dad said. ‘What about water and heating? Is there electricity?’

‘Plenty. A shower and toilet all to yourselves. Everyone eats at the restaurant. They say it’s the best camp in all of Croatia.’

The bus drove through Vešnja at a snail’s pace. At one of the stops, two guys dressed like freaks got on. One was wearing a red checked shirt. The other, a purple T-shirt and a pair of cut-offs. They were dressed like Neno, and I picked up the bag from the empty seat and moved it onto my lap. But they walked past and sat at the very back.

Instead a bald guy pushed his way towards the empty spot. He thumped down onto the seat with a snort and nodded at me:

‘Hot, eh?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Really hot!’

He unfolded a paper bag and started munching away on a greasy burek with cheese.

‘Mirko,’ he introduced himself to the neighbouring brunette, with flakes of puff pastry sprinkling down over his lap.

I tried to block out everyone around me, their gazes, voices and smells. Staring out at me from the leather cover of Mum’s backrest was a huge U, written in black felt pen. I closed my eyes and remembered a viaduct in Split, where Dad and I had seen one that was even larger.

‘A few years ago, they would send you to jail for doing something like that,’ Dad had said. ‘Now people brag about being a fascist Ustashe! Democracy? To hell with them and their democracy!’

Majbule was situated on a hill. We were exiting the only roundabout in town when I spotted the bay and the small peninsula. Before the camp had been established, the bus would terminate here, according to Ivka. Now, twice a day, the bus continued down through the narrow one-way streets to the refugee camp in the bay.

‘The camp’s seen better days,’ Ivka said, ‘and it's no wonder: five hundred arses, one thousand feet, and the same number of hands, all in motion twenty-four hours a day – they leave their mark! Greasy fingerprints everywhere. Broken chairs, scratched tables. Beneath the fig trees and behind the bushes, it stinks of piss.’

‘Really?’ Mum asked in surprise.

‘You know our people. Most of them are from the countryside. They piss anywhere they can. On the other hand, the city people make a lot of racket. The children in particular. Recently there was a boy, he must be half-blind, who ran through a glass door five millimetres thick. Dario was his name. A real brat. And what a racket!’

‘Was he hurt?’

‘Believe it or not: he escaped with only a cut on his forehead. And of course the glass was never replaced.’

‘Why not? What did the owner say? Who owns the holiday camp incidentally?’

‘Before the war this camp was the reserve of majors, colonels, their wives and lovers. The army federation, trade union, whatever it's called, Serbian, they built it back in the day.’

‘Ah, I see.’

‘But all the elegant receptionists are long gone now. The former caretakers and cleaning ladies work behind the counter now. They don’t lift a finger. Just sort the post, answer the phones and wait for further instructions from those “higher up the system”’.

‘Just like the rest of us,’ Dad said with a smile.

‘Yes. And those “higher up the system” have far more important things to do than discuss the army federation’s former holiday camp. The officers, be they Serbian or Croatian, don’t have much time for a holiday these days.’

‘No, that’s true,’ Dad laughed. ‘Unfortunately.’

Funny, I thought. Were it not for the YPA, The Yugoslav People’s Army, none of us would have seen Majbule or sat on that stinking bus that day. Not just because the YPA had built the camp, but the YPA were also the ones who had driven us out. Since Croatia and Serbia were now independent states and as such ‘did not have the best relationship with one another,’ as Ivka put it, the ownership of the camp was still unsettled. Exactly who had come up with the idea to house refugees from the independent state of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the independent state of Croatia inside this no man’s land, was one of the few things Ivka did not know.

A plump red-headed, and to all appearances, very sleepy receptionist handed us the keys to room 210 in building D1.

We walked across a broad concrete terrace, our movements followed by a group of old women. They were sitting on the benches of the terrace, crocheting in grand style.

‘Hello there!’

‘Hello!’

‘Is this D1?’

‘Yes.’

Then up the stairs and down the corridor, where the greyish wall-to-wall carpeting reeked of synthetic material and rubber.

Dad unlocked the door and we went inside. He shook his head at the sight of the table and the three perfectly made beds.

‘Look at this! Karadžić has damn well screwed me over,’ he said with a wry smile. ‘He’s forced me to go on holiday!’

Mum peeked inside a couple of drawers and opened the door to the brown, built-in wardrobe. She placed the few rags we managed to bring with us on a shelf and started to cry. Dad signalled to me – ‘act like nothing is wrong’ – then went into the bathroom.

‘It looks good!’ he shouted as he rattled the shower hose. ‘We’ve got water. Hot water!’

I stepped out onto the balcony so Mum could cry in peace. Took my first look at the windows and balconies of D2. Then over at the water, the island and the peninsula, which I could just make out from our balcony.

I went back inside, grabbed our red Sanyo cassette player from Neno’s bag and unwound the cord. Sanyo is the name of a Japanese company that makes cassette players, and had no connection to the Serbo-Croat verb sanjati, to dream. I knew that. I also knew I was not dreaming, even though everything around me seemed rather surreal and distant. It was as though a thin shell of glass had been placed around me and separated me from everything I could smell, hear and see: the smell of laundry from the neighbouring balcony, the yellowed wall socket above the bed, my mum’s quiet and fading tears and the immediate, high-pitched sound you hear when you press play.

POLITICS

I only had one cassette with me. I had not had time to grab the rest. White Button, best-of. Pretty good. It was in the player the day we had to pack our things and leave.

‘Stop!’

In the middle of ‘Blues For My Ex’, Bregović’s solo was interrupted.

‘My turn now,’ Dad said and grabbed the tape player. ‘Now then.’

‘Hey, what are you doing, man?’

‘I’ve been in that rumbling wreck of a bus all day, son. I want some peace and quiet now, I don’t want to be tormented by your Indians! The news is going to be on in a moment.’

By the door to the corridor, directly across from the bathroom, there was a mirror with a shelf at the bottom. I ran my hand through my hair, checked my teeth and got a proper downer at the sight of my stupid yellow T-shirt. Not very rock’n’roll. All my best clothes were back home. I should have packed myself. Not left it to Mum during the hurried chaos of the day.

‘Oww!’

‘Now what?’

‘My neck. It hurts like hell! It’s almost like it’s … on backwards.’

‘I’m sure it will pass,’ Mum said. ‘It could have been worse.’

Yeah, I thought. My right ear could have been damaged by the explosion. And that would have been a downer. Having to listen to the coolest rock with only one ear.

As I stepped out onto the terrace between D1 and D2, it felt like everyone was staring at me – the old women on the benches and everyone sitting on the balconies. In several places the Croatian flag was draped over the railings, and blasting from one of the open windows in D2 was the year’s big hit, ‘Čavoglave’. On b

oth the radio and TV, they played it over and over again, so not a living soul avoided getting it in their head. One day at Uncle’s flat, sitting in front of the telly, I caught myself humming along: ‘Our hand will reach you even in Serbia!’

The terrace between D1 and D2 had the reception building at one end and a long set of stairs at the other. The stairs led down to a paved path that was shaded by a row of twisted pine trees. Beyond and below the trees was the beach, with the white shiny cliffs of the bay and scattered holidaymakers.

I walked down the stairs and turned right. Dry pine needles crunched under my feet. The path led me to a building, which at first glance was identical to the other two, but it appeared completely abandoned. There were beds with mattresses in the rooms on the ground floor, but no duvets or linen. A sign by the entrance read D3.

I turned and strolled back – past D2, D1 and on towards the restaurant, which was a little further down the path and offered a view of the sea. Between the trees I could just make out the flat cliffs and the people lying on them. It was impossible to see which ones were refugees and which ones were tourists. Two woman passed me. One was topless. I noticed it too late.

Below the restaurant’s terrace was the only stretch of beach in the entire bay where there were no cliffs. A couple of fat children were playing with the dazzling white rocks. They were speaking German and throwing the rocks in the water, a turquoise green that reminded me of one of Dad’s shirts. I took in the smell of resin, rotten seaweed and summer, and suddenly felt like swimming.

At the end of the only pier on the beach I spotted the two long-haired guys from the bus. One of them took a run-up and jumped into the water. The other one sat on the pier with his toes dipped in the water.

‘Hey, Samir,’ a gangling woman shouted from the point where the beach and the pier met. ‘Dad and I are heading back to the room!’

She had a strong Bosnian accent, and the guy with his toes in the water turned and replied in an even stronger one:

‘Fine! But why are you telling me? We’re staying!’

‘Remember dinner’s at six, you too Damir!’

Ukulele Jam

Ukulele Jam